Introduction

Food fraud, which can be aptly described as “the deliberate substitution, addition, tampering, or misrepresentation of food, food ingredients, or food packaging, or false or misleading statements made about a product for economic gain”, is a significant issue [3]. Primarily driven by economic motives, food fraud not only undermines food safety and public trust but also inflicts a hefty cost on the global food industry, amounting to €30 billion a year. Moreover, it exposes oversight gaps in food supply chains, leading to a severe erosion of consumer trust. In addition to these issues, vendors face high costs due to product recalls when fraud is detected [5].

Drawing upon the research of key authorities like the FAO, this article delves into the realm of food fraud, examining its repercussions on both the food industry and consumers. It also investigates the measures currently in place to prevent it.

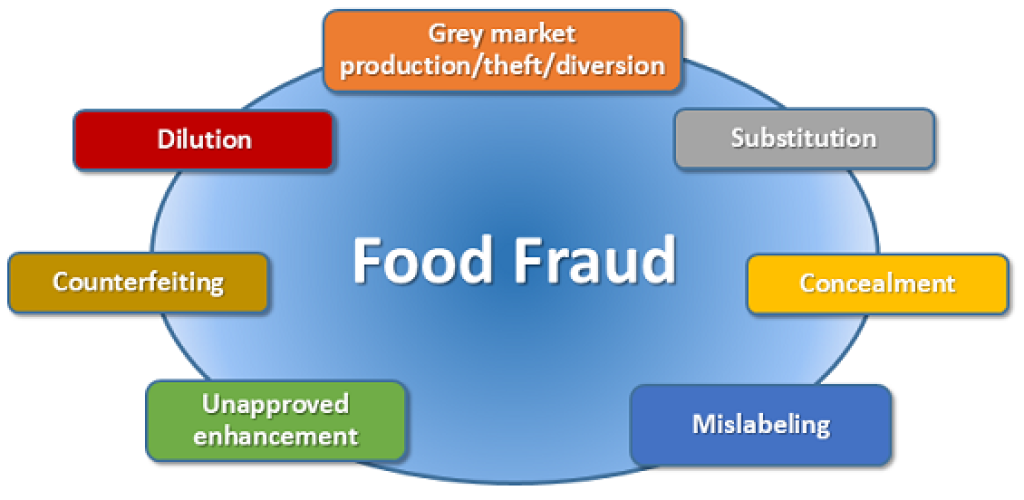

Types of food fraud

A significant proportion of food fraud incidents involve high-value commodities. Such fraudulent activities could encompass altering the product’s labeling, concealing the true quality of the product, or even adulterating the product with foreign substances to artificially enhance its perceived quality [1]. Here are some examples:

Honey – To lower the price of production, honey is often added with cheaper sweeteners, including corn syrup, sugar beet syrups, or cane sugar.

Olive oil – To lower production prices, some companies dilute olive oil with cheaper substances or mask other vegetable oil to pass as olive oil.

Spices – To lower the price of production, expensive spices, like saffron or chili, are bulked up with other cheaper spices, plant material, or dyes [1].

(in)Famous examples of food fraud

Although food fraud is a common issue in the food industry, with numerous cases going unreported or overlooked by the public, there have been certain incidents that have gained significant attention in the past. These cases have served to highlight the extent and impact of this problem [1] [7]:

- In 2012, a scandal struck in Europe: after beefburgers tested positive for horse meat presence in the UK, a lot of other products were discovered to contain horse meat not declared on the label. The scandal cost Tesco a market value loss of €360 million.

- In 2008, in China, a tragedy resulted from melamine-adulterated infant formula. Melamine is a synthetic chemical that if consumed can lead to kidney failure, resulting in illness in at least 300,000 infants and the death of six of them [1] [7].

Global statistics on food fraud

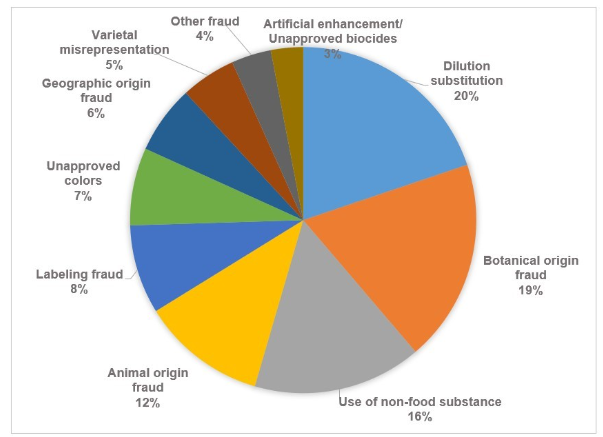

In 2024, a research paper was published sharing data from a database of food fraud records from 1980 to 2022. Figure 2 offers an overview of food fraud types in 2022 [6] According to the publishers, this relevant statistical information can be extrapolated [3]:

- Approximately 34% to 60% of records included potentially hazardous adulterants.

- Dairy, seafood, meat, poultry, herbs, spices, seasonings, milk, cream, and alcoholic beverages were the groups with the most incidents.

- India recorded the most incidents, followed by China, the United States, Italy, the United Kingdom, and Pakistan [3] [6].

The costs and impact of food fraud

Food fraud has far-reaching impacts that can harm the food industry, consumers, and the economy and even hinder food security. According to food safety authorities, these are the repercussions of food fraud globally [4] [8]:

- Health risks – Unidentified allergens or hazardous materials may be added to products, endangering the health of consumers.

- Economic impact – Since food fraud is designed to prevent discovery, it is difficult to estimate its frequency or economic impact. Experts estimate that fraud costs could be as high as €30 billion per year excluding related healthcare costs.

- Trust erosion – Food fraud impacts consumers’ trust in the food industry and regulatory bodies.

- Nutrition – Some studies have found that in areas with limited food security, food theft can lead to malnutrition [4] [8].

Tools to fight food fraud

A robust legislative framework is the most effective tool in combating food fraud. By addressing this issue, economic costs can be diminished, consumer health and trust can be improved, and food insecurity can be mitigated. This proactive approach not only safeguards public health but also restores faith in the integrity of food supply chains. According to the FAO, the first step that should be taken by governments is to adopt a clear definition of food fraud. Additionally, the implementation of food fraud vulnerability assessments is recommended as a strategy to improve the private sector’s ability to prevent such fraud.

Lastly, additional steps could involve establishing standards for various food categories, implementing food labeling regulations, and enacting consumer protection laws. For a more comprehensive understanding of legal interventions against food fraud, refer to the complete FAO report [5].

Innovative technologies

Effective control and enforcement are crucial for the success of legal interventions against food fraud. Moreover, officials conducting these inspections must possess the technical expertise to discern fraudulent products, a task where technological advancements can prove beneficial. Innovative technological solutions described by FAO include [5]:

- Portable testing devices – To test samples directly and connected to reference databases to which they could compare the results from the analyzed samples.

- DNA barcoding – To identify species from a short genetic sequence.

- Blockchain technology – To assist traceability and transparency [5].

iMIS Food Updates

iMIS Food is an example of how innovative technologies can assist in food fraud prevention. This knowledge-driven platform is designed for Food Safety Assurance, enabling food businesses to independently manage their Food Safety. The platform assists companies in demonstrating compliance with Food Safety, EU Food legislation, and quality standards. System enhancements are rolled out through “iMIS Food Updates”.

iMIS Food Updates is a valid tool against food fraud as it keeps you informed about:

- Food Safety Hazards overview, library, and updates

- Food Fraud overview, library, and updates

- EU Legislation overview, library, and updates

- Food Safety Standards overview, library, and updates

- Food Training material and updates

- iMIS Food generic overview, library, and updates

Sources

- Center for Food Safety and Applied. (2023, January 31). Economically motivated adulteration (Foodfraud). U.S. Food And Drug Administration. https://www.fda.gov/food/compliance-enforcement-food/economically-motivated-adulteration-food-fraud

- EFSA. (2020). FoodFraud | Knowledge for policy. EFDA. https://knowledge4policy.ec.europa.eu/food-fraud-quality/topic/food-fraud_en

- Everstine, K., Chin, H. B., Lopes, F. A., & Moore, J. C. (2024). Database of FoodFraud Records: Summary of Data from 1980-2022. Journal of Food Protection, 100227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfp.2024.100227

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (n.d.). Foodfraud – its impact on consumer trust and possible health consequences. FAO. https://www.fao.org/food-safety/news/news-details/en/c/1661886/

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. (2021). FoodFraud – Intention, Detection and Management. In Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/3/cb2863en/cb2863en.pdf

- FoodChain ID. (2023, November 6). Food Fraud Database – FoodChain ID. https://www.foodchainid.com/products/food-fraud-database/

- The 5 biggest foodfraud cases ever pulled off | Ideagen. (n.d.). https://www.ideagen.com/thought-leadership/blog/the-5-biggest-food-fraud-cases-ever-pulled-off

- Thinking about the future of food safety. (2022). In FAO eBooks. https://doi.org/10.4060/cb8667en

Related articles to Exposing food fraud: the new hidden truth

Many customers and visitors to this page 'Exposing food fraud: the new hidden truth' also viewed the articles and manuals listed below: