The Safe Food Imperative

The Safe Food Imperative report is a call for greater prioritization of Food Safety and public targeted investment in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). Food Safety is a shared responsibility between consumers, food businesses, farmers, and public agencies, therefore governments cannot act alone to ensure it.

SDG’s

Food Safety is part of the Sustainable Development Goals, and it is vital in achieving the following goals: ending poverty and hunger as well as promoting good health and well-being, and also contributes indirectly to gender equality, clean water and sanitation, decent work and economic growth and sustainable cities and communities (goals 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 8 and 11).

Furthermore, Food Safety is embedded in Food Security, as safe food is required to meet nutritional diet needs. Unsafe food inhibits nutrient uptake and thus makes it unsuitable for human consumption. Food safety hazards can lead to food losses and thus reduce the availability of food, which is one of the Food Security pillars.

The public health burden and economic costs

As the study highlights, Food Safety hazards are a major public health challenge that has considerable socioeconomic consequences. Most developing countries lack reliable data on foodborne hazards as well as the prevalence of foodborne diseases. Therefore, evidence on this is limited and difficult to be accessed by policymakers or different stakeholders.

Low and middle-income countries (LMICs) fall within the transitioning stage of the Food Safety life cycle presented in The Safe Food Imperative report. According to this, the socioeconomic burden related to Food Safety increases when countries move from low to middle-income stages. In countries with low levels of economic growth, the economic costs of foodborne diseases are related to informal domestic markets, whereas, in the middle-income countries, the costs put emphasis on the formal market (especially on the agri-food exports) and are more visible.

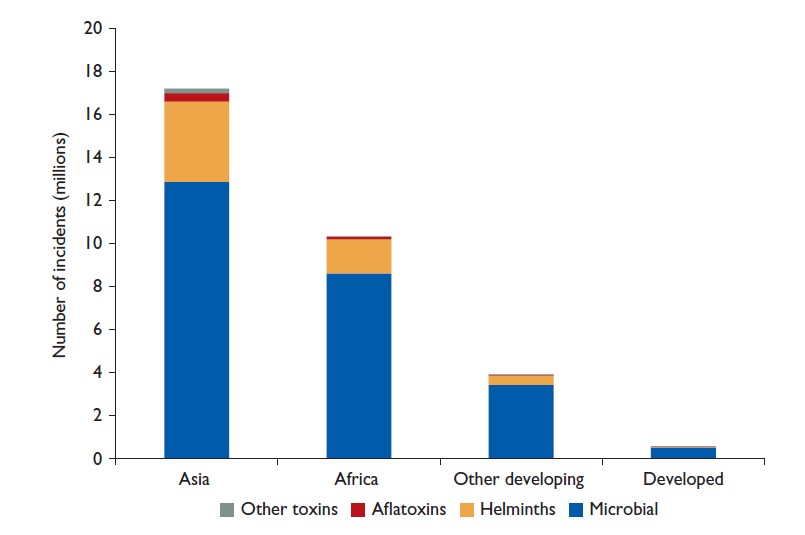

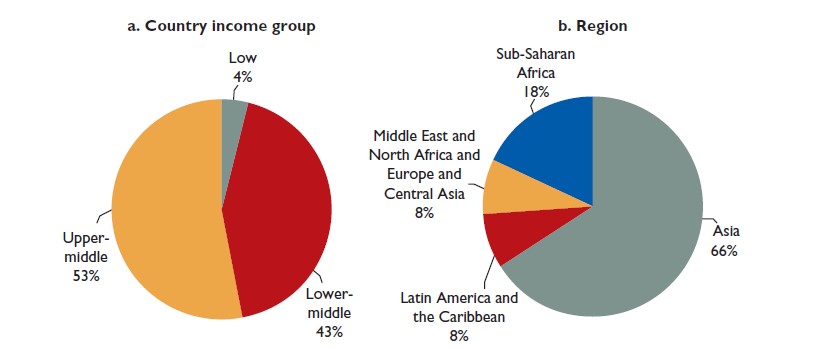

According to this report, Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa register the highest incidence of foodborne diseases along with the highest rate of deaths due to this. Figure 2 highlights the global burden of foodborne diseases and nearly 80 percent is linked with microbial pathogens. Additionally, figure 3 illustrates the productivity losses from foodborne diseases by income and region. It can be seen that LMICs registered 43 percent losses in 2016 and Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa account for most of the losses per region. Assessing the costs in these countries is challenging as there are limitations, such as lack of data or poor-quality data. Nevertheless, based on the few studies on national records (broad assumptions and extrapolations) estimates of the costs have been made and this provided valuable insights.

Food Safety risks in LMIC in domestic markets

Although the agri-food systems in LMICs are transforming, traditional sectors prevail in the food value chain. Traditional food markets in LMICs consist of street food, wet markets as well as informal and formal small food companies. Studies show evidence that in these markets Food Safety practices are likely to be weak and thus the incidence of foodborne diseases increases. According to the report, 85-95 percent of the Sub-Saharan African domestic market demand is supplied by informal sectors. Moreover, in the same region, the food purchased through the informal market is projected to decline by only 50-70 percent by 2040.

Another Food Safety consequence associated with the modernization of food systems in LMICs is Food Fraud, for instance, adulteration and tampering. Food producers are inclined to use such practices to enhance food products or to find cheaper alternatives for their ingredients. Food products can be contaminated with dangerous pesticides, additives, veterinary drugs, or other substances which can harm the consumers.

Besides the problem of foodborne diseases, improper Food Safety practices, due to lack of Food Safety management capacity, impact the agri-food chain in the LMICs. Currently, the importance of compliance with Food Safety regulations and standards in these countries is growing. In order to access global markets, LMICs must meet stricter Food Safety requirements, thus their Food Safety management systems should be upgraded to achieve compliance.

To sum up, Food Safety costs include the public health costs as well as loss of productivity related to foodborne illness along with interruption to food markets, impediments to agri-food exports and the costs of complying with Food Safety regulations and standards. Research states that the costs are greater in LMICs, thus showing the lag in food system capabilities throughout the food market transformation. The analysis of costs done by the World Bank Group in this report indicates that a lack of Food Safety capacity places burdens on public health, the food sector, and the economy.

The status of Food Safety management in developing countries

Based on the report, the lack of evidence on the costs of Food Safety hazards in LMICs led to underinvestment in Food Safety management. The investments in these countries are reactive, meaning that they occur after a foodborne disease outbreak or the imposition of a trade ban. In middle-income countries, the Food Safety management capacity is overwhelmed due to the urbanization and transformation of diets which leads to the increased complexity of Food Safety hazards.

In the past years, diets in LMICs have been shifting from starchy staples towards animal source foods. Furthermore, the supply chains lengthen as the demand for processed foods is rising. Thus, these changes expose consumers to new Food Safety hazards. Domestic markets are still supplied by the informal sector, although the formal sector and more organized food value chains have developed predominantly in the urban areas. In general, Food Safety management systems are underdeveloped in low and middle-income countries, and the existent Food Safety capacity is focusing on exporting and supplying the middle-class markets. Hence, this leads to the rising incidence of FBD (foodborne diseases) in the domestic market.

Food Safety capacity has several dimensions:

- human capital (basic knowledge, specialized expertise, management, leadership as well as communication skills)

- physical infrastructure (safe storage, cold chain, sanitary facilities, processing equipment and laboratory capacity)

- the management systems (enterprises, regulatory control systems, laboratories).

Investments in Food Safety management systems in the public and private sectors, as well as safe food production practices, are drivers that can be stimulated by different stakeholders. For instance, food businesses may be motivated to enhance their Food Safety capacity in order to comply with regulations to avoid recalls and losses or to access global markets. Therefore, these motivations play an important role in the investments in Food Safety capacity. Nevertheless, they also lead the direction of these investments.

Furthermore, benchmarking Food Safety capacity provides valuable indicators about institutional performance along with a motivation for improvements. However, there is no comprehensive benchmark for Food Safety in LMICs. The one used for this study is from World Organisation for Animal Health. Also, many of these studies are not available in the public domain. Yet, the available data on the state of capacity indicate significant gaps between Food Safety management capacity and Food Safety needs in LMICs. Furthermore, there is a clear relationship between a lower capacity and greater foodborne illnesses.

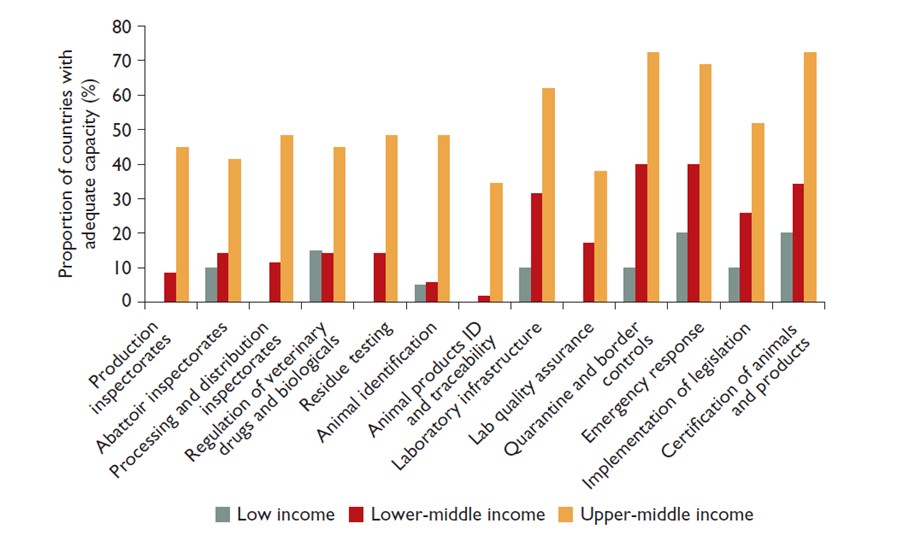

According to the report, the LMICs have underdeveloped Food Safety management systems, particularly in the public sector, see figure 4. For instance, the capacities to manage Food Safety hazards related to animal origins are usually weak. Only 4 out of 34 Sub-Saharan African countries (that have available data) were considered to have adequate capacity for tracing animal and animal products. Furthermore, among the 35 LMICs worldwide, only 6 percent seem to have adequate capacities for animal product identification and traceability and 11-17 percent registered adequate capacities for inspecting distribution facilities and had effective regulations for veterinary drugs.

The report illustrates the shortcomings found in the national food safety systems of LMICs:

- ”The absence of a comprehensive national food safety policy, translating into a lack of prioritization of investments.

- A focus on hazard rather than risk, often leading to the misallocation of resources.

- The presence of many regulations and standards, yet a lack of clarity on the extent to which these are voluntary or mandatory.

- The fragmentation of institutional responsibilities, especially for market surveillance and inspecting food production, processing, and handling facilities.

- Fragmented systems for laboratory testing that do not function as a system and fail to reveal comprehensive inferences on the causes of FBD.

- The lack of effective food safety engagement with consumers, whether in relation to education, risk communication, and other matters.

- The failure to empower and incentivize the private sector to deliver food safety.

- The lack of consistent and transparent border measures to address growing food imports”.

To put it briefly, most of the LMICs have weak food safety systems due to inadequate policy and underinvestment. Furthermore, Food Safety governance in these countries is also weak. Although many of these countries have strong Food Safety management capacity, the emphasis is on the formal sector which supplies the wealthiest consumers whereas the sector serving the poor, lacks infrastructure and services. Additionally, the discourse on Food Safety has focused on trade. Complying with stringent Food Safety regulations and standards to enter the global market has been the main objective of investments in LMICs.

Strengthening Food Safety management

Most of the LMICs have laws and regulations related to Food Safety as well as authorities responsible to enforce these laws, however, this is fragmented. Moreover, even fewer countries have proper Food Safety policy frameworks. Without this policy framework, investments in building as well as maintaining Food Safety management capacity tend to be inadequate and thus, Food Safety governance becomes weak and fragmented, leading to poorly targeted investments.

The report makes the following recommendations on the steps toward a more effective Food Safety policy framework:

- ”Adopt a food safety system perspective and an inclusive concept of food safety management

- Shift the focus from hazards to risks and address risks at every stage of the agri-food chain

- Shift from a reactive to a preventive orientation that anticipates risks and opportunities

- Adopt a more structured and consistent approach to prioritized decision making”

Furthermore, the report makes the following recommendations on better implementation of this Food Safety policy framework:

- ”Reform food safety regulatory practice, shifting from policing to facilitating compliance

- Invest smartly in essential public goods for effective food safety management

- Institutionalize a structured approach to food safety risk management

- Leverage consumer concerns on food safety to incentivize better food business practices”

The report concludes that greater and smarter investments in Food Safety management capacity in LMIC is needed. Furthermore, the investments must be risk-focused and proactive rather than acting when crises occur. Moreover, Food Safety is a shared responsibility, therefore building and maintaining capacity should be the work of both public and private sectors. In the report, clear calls for actions are drawn for specific stakeholders.

References

Jaffee, Steven; Henson, Spencer; Unnevehr, Laurian; Grace, Delia; Cassou, Emilie. (2019). The Safe Food Imperative: Accelerating Progress in Low- and Middle-Income Countries. Agriculture and Food Series; Washington, DC: World Bank. World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/30568 License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.

New EU Legislation Tackles Listeria in Ready-to-Eat Foods: What Food Businesses Need to Know

Plastic Food Contact Materials: New EU Rules and BPA Ban

Farm to Fork Strategy: A Guide for Food Businesses

Food Safety Trends to Watch in 2025

Hepatitis A in Dutch Supermarkets: What We Know & How to Prevent Future Outbreaks

Stop Food Recalls: How to Build a Strong Food Safety Culture

Related articles to The Safe Food Imperative By Andrada Mierlut

Many customers and visitors to this page 'The Safe Food Imperative By Andrada Mierlut' also viewed the articles and manuals listed below: